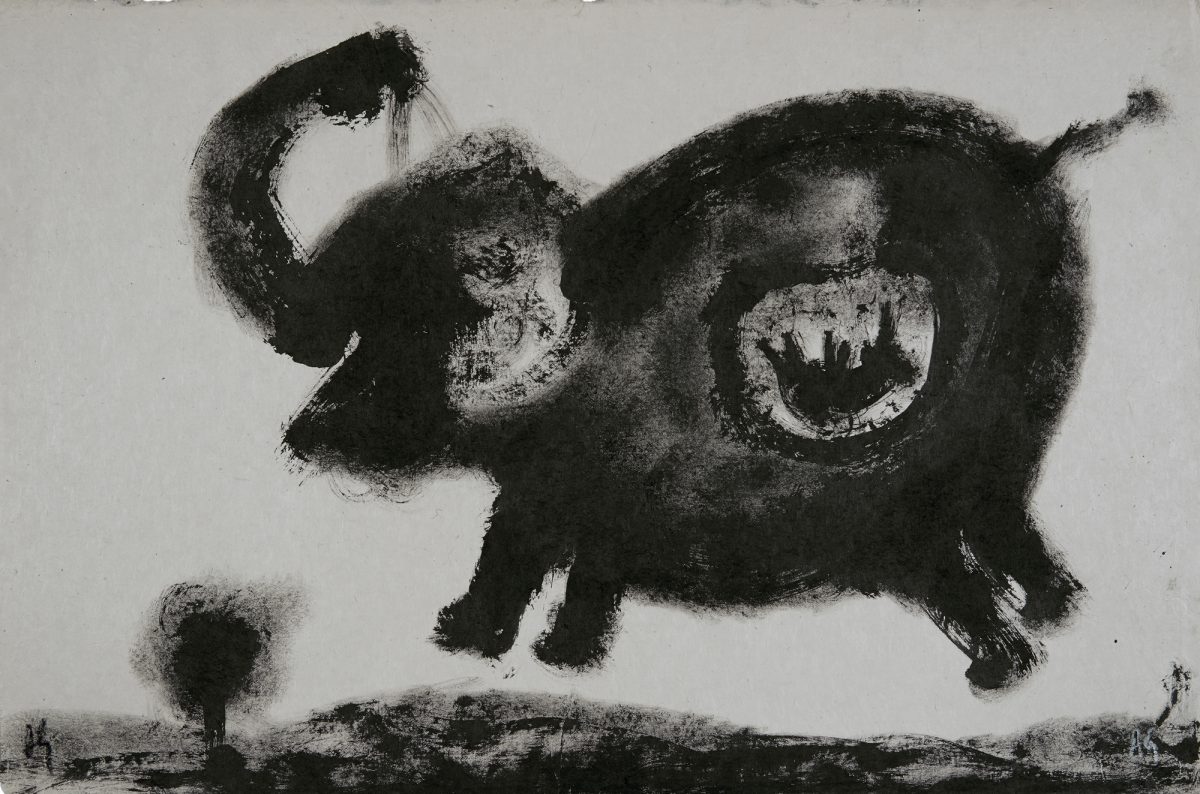

Mon premier cercle

Paintings by Anouk Grinberg

Eléphante qui vole de joie. 2015

Painting by Grinberg

Indian ink on Tibetan paper

76 x 51 cm

© Xavier Pruvot

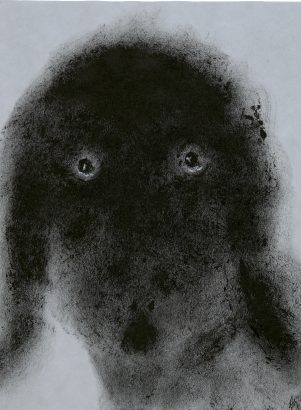

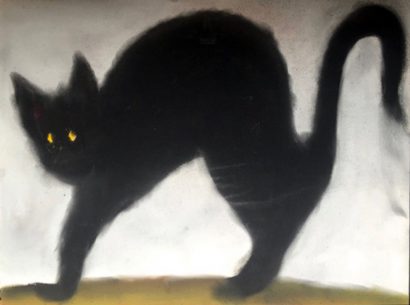

In the anouk’s drawings — I don’t resort to “the” to deify an actress as the French do, when she so wittingly effaces herself, overshadowed by the animals she draws; I omit her name’s majuscule, so that she may better be seen as one of them; I write the anouk as one would say the bear, the bird — we come back to our senses, as beasts spring from frames, that were never enclosures. For we cannot picture their borders, since we abandon the bounds separating humans and animals. The anouk sees, traces, draws, paints, starting with her own species; then on to all the living. In her gaze, or that of a goat or a dog, one reads the melancholy or the bewilderment, often a combination of the two. I couldn’t find another way to view this world and these times, if I tried.

These animals know; they know our excesses, our limits, our mistakes, our accidents, our defeats. They know who we are. They know they have been betrayed, they remain betrayed. Our caresses breed domination, they know it, know they are being patronized into our predators’ nets. Silently, they interrogate us. Demanding no explanation. Incriminating no one. They have an elegance, a genius. But they know and we know. Each in their birthday suit, the animals drawn by the anouk recall an ancestral or nascent solidarity, when human beasts did (or will) speak on our behalf. Just as when we were children, the wolves passed through the bedroom counselling us fearlessly not to grow up, when the nearest pasture’s cows carried friendship in their horns, when the brotherly deer leapt out in the night to open a ladder to reality. Before our social identity ravaged our entire animal being, we moved among the beasts choosing the one we would make a totem, an assumed identity. Tenderness, we used to say. Esteem. Gratitude.

Hunting Lion with a Bow, the documentary by Jean Rouch, shot between 1958 and 1965, takes us on the Gurma bank of the Niger, in “nowhere land”, in the bush further than far, where only the Fulani shepherds lived. The Fulani believed the lion vital to the herd; the herd could only survive with the lion. They could identify each lion by studying their tracks. If a lion ate too many cows, it was considered a killer and, reluctantly, hunted down. A hereditary cast, the Songhaï alone were authorised to track the feline. Preparing for the hunt, they observed an exacting protocol; killing the lion did not occur without some ceremony; the deed required precaution and solemnity. In the course of the film, as the Songhaï track the killer lion, we witness the death of a lion cub. Not the one being hunted. Tahiru, head of the hunters, then kneels asking the animal’s pardon and praying to hasten its death. A ritual for the release of the soul. The soul of a lion.

The drawings of the anouk, where the heart of a horse neighing is shown, where the baby elephant is visible in the womb, don’t submit to anthropomorphic myths; by a simple line, our condescendence or scorn recalls that animal sensibility. The triumphant childlike quality, in its complex chiaroscuro, sprouts at the root of elemental truths.

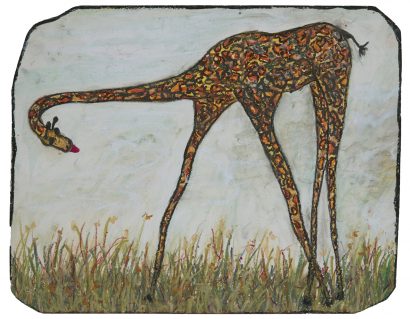

Touched by kind muzzles, pecked by smooth beaks, brought back to our childlike selves, we bow, we beg the pardon of the bird saving its egg or from the cat in the suitcase. For the benefit of the beasts in the world, we recompose a loving discourse, move beyond melancholy and beat bewilderment; take as an example this elephant juggling the sun or that giraffe mocking herself by sticking out her tongue. Hope for the lightness that is contagious, find the grace in the distance that restores. Tempt joy, while brutes and cynics turn joy into a dead viper.

Tempt joy.

The drawings of the anouk promise that a day will come, not far from a cemetery of threats, in this nowhere land, the only one left to live in, where animals will take human beings as totems, when we are finally worthy.

Fabrice Melquiot, 2016

Translated by Ilsa Carter and Pierre Guglielmina

Pastel on cotton paper, 49 x 64 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Oil and Indian ink on Tibetan paper , 68 x 103 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Oil on mounted paper, 32 x 24 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Indian ink on paper, 24 x 32 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Acrylic on paperboard, 33 x 24 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Acrylic on canvas board, 15 x 20 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Embroidery on antique silk doily, 23 x 23 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Pastel on paper, 18 x 13 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Pastel on paper, 40 x 30,5 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Pastel on paper, 20 x 30 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Pastel on paper, 77 x 55 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Pastel on paper, 32 x 24 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Oil on paper, 30 x 42 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Oil on paper, 38 x 30 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Indian ink on tibetan paper, 70 x 102 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Indian ink on paper, 32 x 24 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Pastel on cotton paper, 40 x 31 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Ink and watercolor on Tibetan paper, 31 x 29 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Indian ink on paper, 26 x 11 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Pastel on paper, 48 x 63 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Pastel on paper, 65 x 47 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Acrylic on mounted carboard, 15 x 10 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Acrylic paint on tensed paper, 24 x 24 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Indian ink on paper, 26 x 11 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Indian ink on paper, 26 x 11 cm © Xavier Pruvot

Acrylic on paper, 30 x 23 cm © Xavier Pruvot